Radical Republican (USA) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Radical Republicans (later also known as " Stalwarts") were a faction within the Republican Party, originating from the party's

The Radicals were heavily influenced by religious ideals, and many were Christian reformers who saw slavery as evil and the Civil War as God's punishment for slavery.

The term "

The Radicals were heavily influenced by religious ideals, and many were Christian reformers who saw slavery as evil and the Civil War as God's punishment for slavery.

The term "

The Radical Republicans opposed Lincoln's terms for reuniting the United States during

The Radical Republicans opposed Lincoln's terms for reuniting the United States during

The Radical plan was to remove Johnson from office, but the first effort at the impeachment trial of President Johnson went nowhere. After Johnson violated the Tenure of Office Act by dismissing

The Radical plan was to remove Johnson from office, but the first effort at the impeachment trial of President Johnson went nowhere. After Johnson violated the Tenure of Office Act by dismissing

During

During

excerpt

als

online review

* * Pulitzer Prize. * * Hostile * Pulitzer Prize. * A major biography completed by

''Harper's Weekly''

news magazine

Barnes, William H., ed. ''History of the Thirty-ninth Congress of the United States.'' (1868)

useful summary of Congressional activity. * Blaine, James.''Twenty Years of Congress: From Lincoln to Garfield. With a review of the events which led to the political revolution of 1860'' (1886). By Republican Congressional leade

full text online

* Fleming, Walter L. ''Documentary History of Reconstruction: Political, Military, Social, Religious, Educational, and Industrial'' 2 vol (1906). Uses broad collection of primary sources; vol 1 on national politics; vol 2 on state

full text of vol. 2

* Hyman, Harold M., ed. ''The Radical Republicans and Reconstruction, 1861–1870''. (1967), collection of long political speeches and pamphlets. *

'' The Political History of the United States of America During the Period of Reconstruction'' (1875)

large collection of speeches and primary documents, 1865–1870, complete text online.

Charles Sumner, "Our Domestic Relations: or, How to Treat the Rebel States" ''Atlantic Monthly'' September 1863

early Radical manifesto

online

highly detailed compendium of facts and primary sources; details on every state * ''American Annual Cyclopedia...for 1869'' (1870

online edition

''Appleton's Annual Cyclopedia...for 1870''

(1871)

''American Annual Cyclopedia...for 1872''

(1873) * ''Appleton's Annual Cyclopedia...for 1873'' (1879

online edition

''Appleton's Annual Cyclopedia...for 1875''

(1877) * ''Appleton's Annual Cyclopedia ...for 1876'' (1885

online edition

''Appleton's Annual Cyclopedia...for 1877''

(1878) {{Reconstruction era 1854 establishments in the United States 1877 disestablishments in the United States * American Civil War political groups Factions in the Republican Party (United States) Reconstruction Era Civil rights in the United States

founding

Founding may refer to:

* The formation of a corporation, government, or other organization

* The laying of a building's Foundation

* The casting of materials in a mold

See also

* Foundation (disambiguation)

* Incorporation (disambiguation)

In ...

in 1854, some 6 years before the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

, until the Compromise of 1877

The Compromise of 1877, also known as the Wormley Agreement or the Bargain of 1877, was an unwritten deal, informally arranged among members of the United States Congress, to settle the intensely disputed 1876 presidential election between Ruth ...

, which effectively ended Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*'' Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

. They called themselves "Radicals" because of their goal of immediate, complete, and permanent eradication of slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

, without compromise. They were opposed during the War by the Moderate Republicans (led by President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

), and by the pro-slavery and anti-Reconstruction Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

. Radicals led efforts after the war to establish civil rights for former slaves and fully implement emancipation. After weaker measures in 1866 resulted in violence against former slaves in the rebel states, Radicals pushed the Fourteenth Amendment and statutory protections through Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of a ...

. They opposed allowing ex-Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

officers to retake political power in the Southern United States

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, or simply the South) is a geographic and cultural region of the United States of America. It is between the Atlantic Ocean ...

, and emphasized equality, civil rights and voting rights for the "freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), abolitionism, emancipation (gra ...

", i.e., former slaves who had been freed during or after the Civil War by the Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the Civil War. The Proclamation changed the legal sta ...

and the Thirteenth Amendment.

During the war, Radical Republicans opposed Lincoln's initial selection of General George B. McClellan

George Brinton McClellan (December 3, 1826 – October 29, 1885) was an American soldier, Civil War Union general, civil engineer, railroad executive, and politician who served as the 24th governor of New Jersey. A graduate of West Point, McCl ...

for top command of the major eastern Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the principal Union Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the surrender of the Confedera ...

and Lincoln's efforts in 1864 to bring seceded Southern states back into the Union as quickly and easily as possible. Lincoln later recognized McClellan's weakness and relieved him of command. The Radicals passed their own Reconstruction plan through Congress in 1864, but Lincoln vetoed it and was putting his own policies in effect as military commander-in-chief when he was assassinated

Assassination is the murder of a prominent or important person, such as a head of state, head of government, politician, world leader, member of a royal family or CEO. The murder of a celebrity, activist, or artist, though they may not have a ...

in April 1865. Radicals pushed for the uncompensated abolition of slavery, while Lincoln wanted to pay slave owners who were loyal to the Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

. After the war, the Radicals demanded civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life of ...

for freed slaves, including measures ensuring suffrage. They initiated the various Reconstruction Acts

The Reconstruction Acts, or the Military Reconstruction Acts, (March 2, 1867, 14 Stat. 428-430, c.153; March 23, 1867, 15 Stat. 2-5, c.6; July 19, 1867, 15 Stat. 14-16, c.30; and March 11, 1868, 15 Stat. 41, c.25) were four statutes passed duri ...

as well as the Fourteenth Amendment and limited political and voting rights for ex-Confederate civil officials and military officers. They keenly fought Lincoln's successor, Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a Dem ...

, a slave owner from Tennessee who favored allowing Southern states to decide the rights and status of former slaves. After Johnson vetoed various congressional acts favoring civil rights for former slaves, they attempted to remove him from office through impeachment

Impeachment is the process by which a legislative body or other legally constituted tribunal initiates charges against a public official for misconduct. It may be understood as a unique process involving both political and legal elements.

In ...

, which failed by one vote in 1868

Events

January–March

* January 2 – British Expedition to Abyssinia: Robert Napier leads an expedition to free captive British officials and missionaries.

* January 3 – The 15-year-old Mutsuhito, Emperor Meiji of Jap ...

.

Radical coalition

The Radicals were heavily influenced by religious ideals, and many were Christian reformers who saw slavery as evil and the Civil War as God's punishment for slavery.

The term "

The Radicals were heavily influenced by religious ideals, and many were Christian reformers who saw slavery as evil and the Civil War as God's punishment for slavery.

The term "radical

Radical may refer to:

Politics and ideology Politics

*Radical politics, the political intent of fundamental societal change

*Radicalism (historical), the Radical Movement that began in late 18th century Britain and spread to continental Europe and ...

" was in common use in the anti-slavery movement before the Civil War, referring not necessarily to abolitionists, but particularly to Northern politicians strongly opposed to the Slave Power. Many and perhaps a majority had been Whigs, such as William H. Seward

William Henry Seward (May 16, 1801 – October 10, 1872) was an American politician who served as United States Secretary of State from 1861 to 1869, and earlier served as governor of New York and as a United States Senator. A determined oppon ...

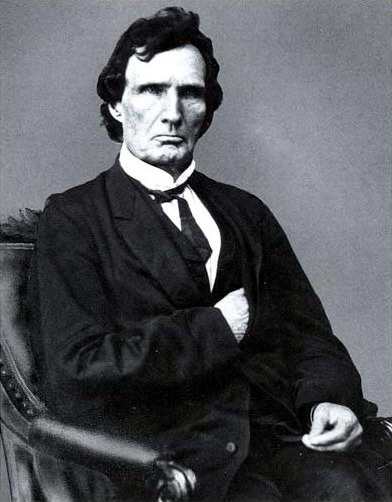

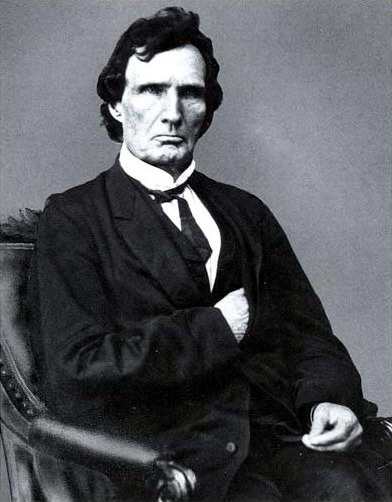

, a leading presidential contender in 1860 and Lincoln's Secretary of State, Thaddeus Stevens

Thaddeus Stevens (April 4, 1792August 11, 1868) was a member of the United States House of Representatives from Pennsylvania, one of the leaders of the Radical Republican faction of the Republican Party during the 1860s. A fierce opponent of sla ...

of Pennsylvania, as well as Horace Greeley

Horace Greeley (February 3, 1811 – November 29, 1872) was an American newspaper editor and publisher who was the founder and newspaper editor, editor of the ''New-York Tribune''. Long active in politics, he served briefly as a congressm ...

, editor of the ''New-York Tribune'', the leading Radical newspaper. There was movement in both directions: some of the pre-war Radicals (such as Seward) became less radical during the war, while some prewar moderates became Radicals. Some wartime Radicals had been Democrats before the war, often taking pro-slavery positions. They included John A. Logan

John Alexander Logan (February 9, 1826 – December 26, 1886) was an American soldier and politician. He served in the Mexican–American War and was a general in the Union Army in the American Civil War. He served the state of Illinois as a st ...

of Illinois, Edwin Stanton

Edwin McMasters Stanton (December 19, 1814December 24, 1869) was an American lawyer and politician who served as U.S. Secretary of War under the Lincoln Administration during most of the American Civil War. Stanton's management helped organize t ...

of Ohio, Benjamin Butler

Benjamin Franklin Butler (November 5, 1818 – January 11, 1893) was an American major general of the Union Army, politician, lawyer, and businessman from Massachusetts. Born in New Hampshire and raised in Lowell, Massachusetts, Butler is best ...

of Massachusetts, Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

of Illinois and Vice President Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a Dem ...

; Johnson would break with the Radicals after he became president.

The Radicals came to majority power in Congress in the elections of 1866 after several episodes of violence led many to conclude that President Johnson's weaker reconstruction policies were insufficient. These episodes included the New Orleans riot

The New Orleans Massacre of 1866 occurred on July 30, when a peaceful demonstration of mostly Black Freedmen was set upon by a mob of white rioters, many of whom had been soldiers of the recently defeated Confederate States of America, leading t ...

and the Memphis riots of 1866

The Memphis massacre of 1866 was a series of violent events that occurred from May 1 to 3, 1866 in Memphis, Tennessee. The racial violence was ignited by political and social racism following the American Civil War, in the early stages of Reco ...

. In a pamphlet directed to black voters in 1867, the Union Republican Congressional Committee stated:

The Radicals were never formally organized and there was movement in and out of the group. Their most successful and systematic leader was Pennsylvania Congressman Thaddeus Stevens

Thaddeus Stevens (April 4, 1792August 11, 1868) was a member of the United States House of Representatives from Pennsylvania, one of the leaders of the Radical Republican faction of the Republican Party during the 1860s. A fierce opponent of sla ...

in the House of Representatives. The Democrats were strongly opposed to the Radicals, but they were generally a weak minority in politics until they took control of the House in the 1874 congressional elections. The "Moderate" and "Conservative" Republican factions usually opposed the Radicals, but they were not well organized. Lincoln tried to build a multi-faction coalition, including Radicals, "Conservatives," "Moderates" and War Democrats as while he was often opposed by the Radicals, he never ostracized them. Andrew Johnson was thought to be a Radical when he became president in 1865, but he soon became their leading opponent. However, Johnson was so inept as a politician he was unable to form a cohesive support network. Finally in 1872, the Liberal Republicans, who wanted a return to classical republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology centered on citizenship in a state organized as a republic. Historically, it emphasises the idea of self-rule and ranges from the rule of a representative minority or oligarchy to popular sovereignty. It ...

, ran a presidential campaign and won the support of the Democratic Party for their ticket. They argued that Grant and the Radicals were corrupt and had imposed Reconstruction far too long on the South. They were overwhelmingly defeated and collapsed as a movement.

On issues not concerned with the destruction of the Confederacy, the eradication of slavery and the rights of Freedmen, Radicals took positions all over the political map. For example, Radicals who had once been Whigs generally supported high tariffs and ex-Democrats generally opposed them. Some men were for hard money and no inflation while others were for soft money and inflation. The argument, common in the 1930s, that the Radicals were primarily motivated by a desire to selfishly promote Northeastern business interests, has seldom been argued by historians for a half-century. On foreign policy issues, the Radicals and moderates generally did not take distinctive positions.

Wartime

After the 1860 elections, moderate Republicans dominated the Congress. Radical Republicans were often critical of Lincoln, who they believed was too slow in freeing slaves and supporting their legal equality. Lincoln put all factions in his cabinet, including Radicals likeSalmon P. Chase

Salmon Portland Chase (January 13, 1808May 7, 1873) was an American politician and jurist who served as the sixth chief justice of the United States. He also served as the 23rd governor of Ohio, represented Ohio in the United States Senate, a ...

(Secretary of the Treasury

The United States secretary of the treasury is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, and is the chief financial officer of the federal government of the United States. The secretary of the treasury serves as the principal a ...

), whom he later appointed Chief Justice, James Speed (Attorney General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general or attorney-general (sometimes abbreviated AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. The plural is attorneys general.

In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have exec ...

) and Edwin M. Stanton

Edwin McMasters Stanton (December 19, 1814December 24, 1869) was an American lawyer and politician who served as U.S. Secretary of War under the Lincoln Administration during most of the American Civil War. Stanton's management helped organize ...

(Secretary of War). Lincoln appointed many Radical Republicans, such as journalist James Shepherd Pike

James Shepherd Pike (September 8, 1811 – November 29, 1882) was an American journalist and a historian of South Carolina during the Reconstruction Era.

Biography

Pike was born in Calais, Maine, and was a journalist in the United States duri ...

, to key diplomatic positions. Angry with Lincoln, in 1864 some Radicals briefly formed a political party called the Radical Democracy Party, with John C. Frémont

John Charles Frémont or Fremont (January 21, 1813July 13, 1890) was an American explorer, military officer, and politician. He was a U.S. Senator from California and was the first Republican nominee for president of the United States in 1856 ...

as their candidate for president, until Frémont withdrew. An important Republican opponent of the Radical Republicans was Henry Jarvis Raymond

Henry Jarvis Raymond (January 24, 1820 – June 18, 1869) was an American journalist, politician, and co-founder of ''The New York Times'', which he founded with George Jones. He was a member of the New York State Assembly, Lieutenant Governor ...

. Raymond was both editor of ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' and also a chairman of the Republican National Committee. In Congress, the most influential Radical Republicans were U.S. Senator Charles Sumner

Charles Sumner (January 6, 1811March 11, 1874) was an American statesman and United States Senator from Massachusetts. As an academic lawyer and a powerful orator, Sumner was the leader of the anti-slavery forces in the state and a leader of th ...

and U.S. Representative Thaddeus Stevens

Thaddeus Stevens (April 4, 1792August 11, 1868) was a member of the United States House of Representatives from Pennsylvania, one of the leaders of the Radical Republican faction of the Republican Party during the 1860s. A fierce opponent of sla ...

. They led the call for a war that would end slavery.Trefousse, ''Thaddeus Stevens: Nineteenth-Century Egalitarian'' (2001)

Reconstruction policy

Opposing Lincoln

The Radical Republicans opposed Lincoln's terms for reuniting the United States during

The Radical Republicans opposed Lincoln's terms for reuniting the United States during Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*'' Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

(1863), which they viewed as too lenient. They proposed an " ironclad oath" that would prevent anyone who supported the Confederacy from voting in Southern elections, but Lincoln blocked it and once Radicals passed the Wade–Davis Bill

The Wade–Davis Bill of 1864 () was a bill "to guarantee to certain States whose governments have been usurped or overthrown a republican form of government," proposed for the Reconstruction of the South. In opposition to President Abraham Linco ...

in 1864, Lincoln vetoed it. The Radicals demanded a more aggressive prosecution of the war, a faster end to slavery and total destruction of the Confederacy. After the war, the Radicals controlled the Joint Committee on Reconstruction

The Joint Committee on Reconstruction, also known as the Joint Committee of Fifteen, was a joint committee of the 39th United States Congress that played a major role in Reconstruction in the wake of the American Civil War. It was created to "inqu ...

.

Opposing Johnson

After the assassination of United States President Abraham Lincoln,War Democrat

War Democrats in American politics of the 1860s were members of the Democratic Party who supported the Union and rejected the policies of the Copperheads (or Peace Democrats). The War Democrats demanded a more aggressive policy toward the Con ...

Vice President

A vice president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vice president is on t ...

Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a Dem ...

became President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

. Although he appeared at first to be a Radical, he broke with them and the Radicals and Johnson became embroiled in a bitter struggle. Johnson proved a poor politician and his allies lost heavily in the 1866 elections in the North. The Radicals now had full control of Congress and could override Johnson's vetoes.

Control of Congress

After the 1866 elections, the Radicals generally controlled Congress. Johnson vetoed 21 bills passed by Congress during his term, but the Radicals overrode 15 of them, including theCivil Rights Act of 1866

The Civil Rights Act of 1866 (, enacted April 9, 1866, reenacted 1870) was the first United States federal law to define citizenship and affirm that all citizens are equally protected by the law. It was mainly intended, in the wake of the Amer ...

and four Reconstruction Acts

The Reconstruction Acts, or the Military Reconstruction Acts, (March 2, 1867, 14 Stat. 428-430, c.153; March 23, 1867, 15 Stat. 2-5, c.6; July 19, 1867, 15 Stat. 14-16, c.30; and March 11, 1868, 15 Stat. 41, c.25) were four statutes passed duri ...

, which rewrote the election laws for the South and allowed blacks to vote while prohibiting former Confederate Army officers from holding office. As a result of the 1867–1868 elections, the newly empowered freedmen, in coalition with carpetbaggers

In the history of the United States, carpetbagger is a largely historical term used by Southerners to describe opportunistic Northerners who came to the Southern states after the American Civil War, who were perceived to be exploiting the lo ...

(Northerners who had recently moved south) and Scalawags

In United States history, the term scalawag (sometimes spelled scallawag or scallywag) referred to white Southerners who supported Reconstruction policies and efforts after the conclusion of the American Civil War.

As with the term '' carpet ...

(white Southerners who supported Reconstruction), set up Republican governments in 10 Southern states (all but Virginia).

Impeachment

The Radical plan was to remove Johnson from office, but the first effort at the impeachment trial of President Johnson went nowhere. After Johnson violated the Tenure of Office Act by dismissing

The Radical plan was to remove Johnson from office, but the first effort at the impeachment trial of President Johnson went nowhere. After Johnson violated the Tenure of Office Act by dismissing Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

Edwin M. Stanton

Edwin McMasters Stanton (December 19, 1814December 24, 1869) was an American lawyer and politician who served as U.S. Secretary of War under the Lincoln Administration during most of the American Civil War. Stanton's management helped organize ...

, the House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entitles. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often c ...

voted 126-47 to impeach him, but the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

acquitted him in 1868 in three 35-19 votes, failing to reach the 36 votes threshold required for a conviction; by that time, however, Johnson had lost most of his power.

Supporting Grant

GeneralUlysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

in 1865–1868 was in charge of the Army under President Johnson, but Grant generally enforced the Radical agenda. The leading Radicals in Congress were Thaddeus Stevens

Thaddeus Stevens (April 4, 1792August 11, 1868) was a member of the United States House of Representatives from Pennsylvania, one of the leaders of the Radical Republican faction of the Republican Party during the 1860s. A fierce opponent of sla ...

in the House and Charles Sumner

Charles Sumner (January 6, 1811March 11, 1874) was an American statesman and United States Senator from Massachusetts. As an academic lawyer and a powerful orator, Sumner was the leader of the anti-slavery forces in the state and a leader of th ...

in the Senate. Grant was elected as a Republican in 1868

Events

January–March

* January 2 – British Expedition to Abyssinia: Robert Napier leads an expedition to free captive British officials and missionaries.

* January 3 – The 15-year-old Mutsuhito, Emperor Meiji of Jap ...

and after the election he generally sided with the Radicals on Reconstruction policies and signed the Civil Rights Act of 1871

The Enforcement Act of 1871 (), also known as the Ku Klux Klan Act, Third Enforcement Act, Third Ku Klux Klan Act, Civil Rights Act of 1871, or Force Act of 1871, is an Act of the United States Congress which empowered the President to suspend ...

into law.

The Republicans split in 1872

Events

January–March

* January 12 – Yohannes IV is crowned Emperor of Ethiopia in Axum, the first ruler crowned in that city in over 500 years.

* February 2 – The government of the United Kingdom buys a number of forts on ...

over Grant's reelection, with the Liberal Republicans, including Sumner, opposing Grant with a new third party. The Liberals lost badly, but the economy then went into a depression in 1873 and in 1874 the Democrats swept back into power and ended the reign of the Radicals.

The Radicals tried to protect the new coalition, but one by one the Southern states voted the Republicans out of power until in 1876 only three were left (Louisiana, Florida and South Carolina), where the Army still protected them. The 1876 presidential election was so close that it was decided in those three states despite massive fraud and illegalities on both sides. The Compromise of 1877

The Compromise of 1877, also known as the Wormley Agreement or the Bargain of 1877, was an unwritten deal, informally arranged among members of the United States Congress, to settle the intensely disputed 1876 presidential election between Ruth ...

called for the election of a Republican as president and his withdrawal of the troops. Republican Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th president of the United States from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governor ...

withdrew the troops and the Republican state regimes immediately collapsed.

Reconstruction of the South

During

During Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*'' Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

, Radical Republicans increasingly took control, led by Sumner and Stevens. They demanded harsher measures in the South, more protection for the Freedmen and more guarantees that the Confederate nationalism was totally eliminated. Following Lincoln's assassination

On April 14, 1865, Abraham Lincoln, the 16th president of the United States, was Assassination, assassinated by well-known stage actor John Wilkes Booth, while attending the play ''Our American Cousin'' at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C.

S ...

in 1865, Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a Dem ...

, a former War Democrat

War Democrats in American politics of the 1860s were members of the Democratic Party who supported the Union and rejected the policies of the Copperheads (or Peace Democrats). The War Democrats demanded a more aggressive policy toward the Con ...

, became President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

.

The Radicals at first admired Johnson's hard-line talk. When they discovered his ambivalence on key issues by his veto of Civil Rights Act of 1866

The Civil Rights Act of 1866 (, enacted April 9, 1866, reenacted 1870) was the first United States federal law to define citizenship and affirm that all citizens are equally protected by the law. It was mainly intended, in the wake of the Amer ...

, they overrode his veto. This was the first time that Congress had overridden a president on an important bill. The Civil Rights Act of 1866

The Civil Rights Act of 1866 (, enacted April 9, 1866, reenacted 1870) was the first United States federal law to define citizenship and affirm that all citizens are equally protected by the law. It was mainly intended, in the wake of the Amer ...

made African Americans

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

United States citizens, forbade discrimination against them and it was to be enforced in Federal courts. The 14th Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Fourteenth Amendment (Amendment XIV) to the United States Constitution was adopted on July 9, 1868, as one of the Reconstruction Amendments. Often considered as one of the most consequential amendments, it addresses citizenship rights and e ...

of 1868 (with its Equal Protection Clause

The Equal Protection Clause is part of the first section of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. The clause, which took effect in 1868, provides "''nor shall any State ... deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal ...

) was the work of a coalition formed of both moderate and Radical Republicans.

By 1866, the Radical Republicans supported federal civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life of ...

for freedmen, which Johnson opposed. By 1867, they defined terms for suffrage for freed slaves and limited early suffrage for many ex-Confederates. While Johnson opposed the Radical Republicans on some issues, the decisive Congressional elections of 1866 gave the Radicals enough votes to enact their legislation over Johnson's vetoes. Through elections in the South, ex-Confederate officeholders were gradually replaced with a coalition of freedmen, Southern whites (pejoratively called scalawags

In United States history, the term scalawag (sometimes spelled scallawag or scallywag) referred to white Southerners who supported Reconstruction policies and efforts after the conclusion of the American Civil War.

As with the term '' carpet ...

) and Northerners who had resettled in the South (pejoratively called carpetbaggers

In the history of the United States, carpetbagger is a largely historical term used by Southerners to describe opportunistic Northerners who came to the Southern states after the American Civil War, who were perceived to be exploiting the lo ...

). The Radical Republicans were successful in their efforts to impeach United States President Andrew Johnson in the House, but failed by one vote in the Senate to remove him from office.

The Radicals were opposed by former slaveowners and white supremacist

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other Race (human classification), races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any Power (social and polit ...

s in the rebel states. Radicals were targeted by the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and ...

, who shot to death one Radical Congressman from Arkansas, James M. Hinds

James M. Hinds (December 5, 1833 – October 22, 1868) was the first U.S. Congressman assassinated in office. He served as member of the United States House of Representatives for Arkansas from June 24, 1868 until his assassination by the ...

.

The Radical Republicans led the Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*'' Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

of the South. All Republican factions supported Ulysses Grant for president in 1868. Once in office, Grant forced Sumner out of the party and used Federal power to try to break up the Ku Klux Klan organization. However, insurgents and community riots continued harassment and violence against African Americans and their allies into the early 20th century. By the 1872 presidential election, the Liberal Republicans thought that Reconstruction had succeeded and should end. Many moderates joined their cause as well as Radical Republican leader Charles Sumner. They nominated ''New-York Tribune'' editor Horace Greeley

Horace Greeley (February 3, 1811 – November 29, 1872) was an American newspaper editor and publisher who was the founder and newspaper editor, editor of the ''New-York Tribune''. Long active in politics, he served briefly as a congressm ...

, who was also nominated by the Democrats. Grant was easily reelected.

End of Reconstruction

By 1872, the Radicals were increasingly splintered and in the Congressional elections of 1874, the Democrats took control of Congress. Many former Radicals joined the " Stalwart" faction of the Republican Party while many opponents joined the " Half-Breeds", who differed primarily on matters of patronage rather than policy. In state after state in the South, the so-called Redeemers' movement seized control from the Republicans until in 1876 only three Republican states were left: South Carolina, Florida, and Louisiana. In the intensely disputed1876 United States presidential election

The 1876 United States presidential election was the 23rd quadrennial presidential election, held on Tuesday, November 7, 1876, in which Republican nominee Rutherford B. Hayes faced Democrat Samuel J. Tilden. It was one of the most contentious ...

, Republican presidential candidate Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th president of the United States from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governor ...

was declared the winner following the Compromise of 1877

The Compromise of 1877, also known as the Wormley Agreement or the Bargain of 1877, was an unwritten deal, informally arranged among members of the United States Congress, to settle the intensely disputed 1876 presidential election between Ruth ...

(a corrupt bargain): he obtained the electoral votes of those states, and with them the presidency, by committing himself to removing federal troops from those states. Deprived of military support, Reconstruction came to an end. "Redeemers" took over in these states as well. As white Democrats now dominated all Southern state legislatures, the period of Jim Crow laws

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the Sout ...

began, and rights were progressively taken away from blacks.

Historiography

In the aftermath of the Civil War and Reconstruction, new battles took place over the construction of memory and the meaning of historical events. The earliest historians to study Reconstruction and the Radical Republican participation in it were members of theDunning School

The Dunning School was a historiographical school of thought regarding the Reconstruction period of American history (1865–1877), supporting conservative elements against the Radical Republicans who introduced civil rights in the South. It was na ...

, led by William Archibald Dunning

William Archibald Dunning (12 May 1857 – 25 August 1922) was an American historian and political scientist at Columbia University noted for his work on the Reconstruction era of the United States. He founded the informal Dunning School of inter ...

and John W. Burgess.Foner, p. xi. The Dunning School, based at Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

in the early 20th century, saw the Radicals as motivated by an irrational hatred of the Confederacy and a lust for power at the expense of national reconciliation. According to Dunning School historians, the Radical Republicans reversed the gains Abraham Lincoln and Andrew Johnson had made in reintegrating the South, established corrupt shadow governments made up of Northern carpetbagger

In the history of the United States, carpetbagger is a largely historical term used by Southerners to describe opportunistic Northerners who came to the Southern states after the American Civil War, who were perceived to be exploiting the lo ...

s and Southern scalawag

In United States history, the term scalawag (sometimes spelled scallawag or scallywag) referred to white Southerners who supported Reconstruction policies and efforts after the conclusion of the American Civil War.

As with the term '' carpetb ...

s in the former Confederate states, and to increase their power, foisted political rights on the newly freed slaves that they were allegedly unprepared for or incapable of utilizing. For the Dunning School, the Radical Republicans made Reconstruction a dark age that only ended when Southern whites rose up and reestablished a "home rule" free of Northern, Republican, and black influence.Foner, p. xii.

In the 1930s, the Dunning-oriented approaches were rejected by self-styled "revisionist" historians, led by Howard K. Beale

Howard Kennedy Beale (April 8, 1899 – December 27, 1959) was an American historian. He had several temporary appointments before becoming a professor of history at the University of North Carolina in 1935. His most famous student was C. Vann Wo ...

along with W.E.B. DuBois, William B. Hesseltine

William Best Hesseltine (February 21, 1902 – December 8, 1963) was an American historian and politician who became the Socialist Party candidate for U.S. president in 1948. As a historian and professor at the University of Wisconsin–Madi ...

, C. Vann Woodward and T. Harry Williams

Thomas Harry Williams (May 19, 1909 — July 8, 1979) was an American academic and author. For the majority of his academic career between the 1930s to 1970s, Williams taught history at Louisiana State University. While at LSU, Williams was a Boyd ...

. They downplayed corruption and stressed that Northern Democrats were also corrupt. Beale and Woodward were leaders in promoting racial equality and re-evaluated the era in terms of regional economic conflict. They were also hostile towards the Radicals, casting them as economic opportunists. They argued that apart from a few idealists, most Radicals were scarcely interested in the fate of the blacks or the South as a whole. Rather, the main goal of the Radicals was to protect and promote Northern capitalism, which was threatened in Congress by the West; if the Democrats took control of the South and joined the West, they thought, the Northeastern business interests would suffer. They did not trust anyone from the South except men beholden to them by bribes and railroad deals. For example, Beale argued that the Radicals in Congress put Southern states under Republican control to get their votes in Congress for high protective tariffs.

The role of Radical Republicans in creating public school systems, charitable institutions, and other social infrastructure in the South was downplayed by the Dunning School of historians. Since the 1950s, the impact of the moral crusade of the Civil Rights Movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, Racial discrimination ...

led historians to reevaluate the role of Radical Republicans during Reconstruction, and their reputation improved. These historians, sometimes referred to as neoabolitionist because they reflected and admired the values of the abolitionists of the 19th century, argued that the Radical Republicans' advancement of civil rights and suffrage for African Americans following emancipation was more significant than the financial corruption which took place. They also pointed to the African Americans' central, active roles in reaching toward education (both individually and by creating public school systems) and their desire to acquire land as a means of self-support.

Democrats retook power across the South and held it for decades, restricting African American voters and largely extinguishing their voting rights over the years and decades following Reconstruction. In 2004, Richardson argued that Northern Republicans came to see most blacks as potentially dangerous to the economy because they might prove to be labor radicals in the tradition of the 1871 Paris Commune

The Paris Commune (french: Commune de Paris, ) was a revolutionary government that seized power in Paris, the capital of France, from 18 March to 28 May 1871.

During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, the French National Guard had defended ...

or Great Railroad Strike of 1877

The Great Railroad Strike of 1877, sometimes referred to as the Great Upheaval, began on July 14 in Martinsburg, West Virginia, after the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) cut wages for the third time in a year. This strike finally ended 52 day ...

and other violent American strikes of the 1870s. Meanwhile, it became clear to Northerners that the white South was not bent on revenge or the restoration of the Confederacy. Most of the Republicans who felt this way became opponents of Grant and entered the Liberal Republican camp in 1872.

Notable Radical Republicans

* Amos Tappan Akerman: attorney general under the Grant administration who vigorously prosecuted theKu Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and ...

in the South under the Enforcement Acts

The Enforcement Acts were three bills that were passed by the United States Congress between 1870 and 1871. They were criminal codes that protected African Americans’ right to vote, to hold office, to serve on juries, and receive equal protect ...

* Adelbert Ames

Adelbert Ames (October 31, 1835 – April 13, 1933) was an American sailor, soldier, and politician who served with distinction as a Union Army general during the American Civil War. A Radical Republican, he was military governor, U.S. Senato ...

: Governor of Mississippi in 1868–1870 and 1874–1876

* James Mitchell Ashley

James Mitchell Ashley (November 14, 1824September 16, 1896) was an American politician and abolitionist. A member of the Republican Party, Ashley served as a member of the United States House of Representatives from Ohio during the American Civ ...

: representative from Ohio

* John Armor Bingham: representative from Ohio and principal framer of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Fourteenth Amendment (Amendment XIV) to the United States Constitution was adopted on July 9, 1868, as one of the Reconstruction Amendments. Often considered as one of the most consequential amendments, it addresses citizenship rights and ...

* Austin Blair

Austin Blair (February 8, 1818 – August 6, 1894), also known as the Civil War Governor, was a politician from the U.S. state of Michigan, serving as its 13th governor and in its House of Representatives and Senate as well as the U.S. Sena ...

: Governor of Michigan in 1861–1865

* George Sewall Boutwell

George Sewall Boutwell (January 28, 1818 – February 27, 1905) was an Americans, American politician, lawyer, and statesman from Massachusetts. He served as Secretary of the Treasury under President of the United States, U.S. President Ulysses ...

: representative from Massachusetts and Treasury Secretary under President Grant from 1869 to 1873

* William Gannaway Brownlow

William Gannaway "Parson" Brownlow (August 29, 1805April 29, 1877) was an American newspaper publisher, Methodist minister, book author, prisoner of war, lecturer, and politician who served as the 17th Governor of Tennessee from 1865 to 1869 and ...

: publisher of the '' Knoxville Whig'', Tennessee governor and senator

* Rufus Bullock

Rufus Brown Bullock (March 28, 1834 – April 27, 1907) was a Republican Party politician and businessman in Georgia. During the Reconstruction Era he served as the state's governor and called for equal economic opportunity and political rights f ...

: Governor of Georgia 1868–1871

* Benjamin Butler

Benjamin Franklin Butler (November 5, 1818 – January 11, 1893) was an American major general of the Union Army, politician, lawyer, and businessman from Massachusetts. Born in New Hampshire and raised in Lowell, Massachusetts, Butler is best ...

: Massachusetts politician-soldier who was hated by rebels for restoring control in New Orleans

* Zachariah Chandler

Zachariah Chandler (December 10, 1813 – November 1, 1879) was an American businessman, politician, one of the founders of the Republican Party, whose radical wing he dominated as a lifelong abolitionist. He was mayor of Detroit, a four-term sen ...

: senator from Michigan and Secretary of the Interior Secretary of the Interior may refer to:

* Secretary of the Interior (Mexico)

* Interior Secretary of Pakistan

* Secretary of the Interior and Local Government (Philippines)

* United States Secretary of the Interior

See also

*Interior ministry ...

under President Grant

* Salmon P. Chase

Salmon Portland Chase (January 13, 1808May 7, 1873) was an American politician and jurist who served as the sixth chief justice of the United States. He also served as the 23rd governor of Ohio, represented Ohio in the United States Senate, a ...

: Treasury Secretary under President Lincoln and Supreme Court chief justice who sought the 1868 Democratic nomination as a moderate

* Schuyler Colfax

Schuyler Colfax Jr. (; March 23, 1823 – January 13, 1885) was an American journalist, businessman, and politician who served as the 17th vice president of the United States from 1869 to 1873, and prior to that as the 25th speaker of the House ...

: Speaker of the House (1863–1869) and the 17th Vice President of the United States (1869–1873). Was called the Christian statesman

* John Conness

John Conness (September 22, 1821 – January 10, 1909) was a first-generation Irish-American businessman who served as a U.S. Senator (1863–1869) from California during the American Civil War and the early years of Reconstruction. He intr ...

: senator from California

* John Creswell

John Andrew Jackson Creswell (November 18, 1828December 23, 1891) was an American politician and abolitionist from Maryland, who served as United States Representative, United States Senator, and as Postmaster General of the United States app ...

: elected Baltimore Representative to the House in 1863 during the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

, Creswell worked closely under Radical Republican Baltimore Representative Henry Winter Davis and was appointed Postmaster-General by President Grant in 1869, having vast patronage powers appointed many African Americans to federal postal positions in every state of the United States

* Edmund J. Davis: Governor of Texas in 1870–1874

* Henry Winter Davis: representative from Maryland

* Charles Daniel Drake: senator from Missouri

* Reuben Fenton

Reuben Eaton Fenton (July 4, 1819August 25, 1885) was an American merchant and politician from New York (state), New York. In the mid-19th Century, he served as a United States House of Representatives , U.S. Representative, a United States Sen ...

: Governor of New York in 1865–1868

* Thomas Clement Fletcher

Thomas Clement Fletcher (January 21, 1827March 25, 1899) was the 18th Governor of Missouri during the latter stages of the American Civil War and the early part of Reconstruction. He was the first Missouri governor to be born in the state. The ...

: Governor of Missouri in 1865–1869

* John C. Frémont

John Charles Frémont or Fremont (January 21, 1813July 13, 1890) was an American explorer, military officer, and politician. He was a U.S. Senator from California and was the first Republican nominee for president of the United States in 1856 ...

: the 1856 Republican presidential candidate

* James A. Garfield

James Abram Garfield (November 19, 1831 – September 19, 1881) was the 20th president of the United States, serving from March 4, 1881 until his death six months latertwo months after he was shot by an assassin. A lawyer and Civil War gene ...

: House of Representatives leader, less radical than others and president in 1881

* Joshua Reed Giddings

Joshua Reed Giddings (October 6, 1795 – May 27, 1864) was an American attorney, politician and a prominent opponent of slavery. He represented Northeast Ohio in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1838 to 1859. He was at first a member of ...

: representative from Ohio and an early leading founder of the Ohio Republican Party

* Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

: president who signed Enforcement Acts and Civil Rights Act of 1875 while as General of the Army of the United States he supported Radical Reconstruction and civil rights for African Americans

* Galusha A. Grow: representative from Pennsylvania and Speaker of the House 1861 to 1863

* John Parker Hale

John Parker Hale (March 31, 1806November 19, 1873) was an American politician and lawyer from New Hampshire. He served in the United States House of Representatives from 1843 to 1845 and in the United States Senate from 1847 to 1853 and again fro ...

: senator from New Hampshire and one of the first to make a stand against slavery. He was a former Democrat who broke away because of slavery

* Hannibal Hamlin

Hannibal Hamlin (August 27, 1809 – July 4, 1891) was an American attorney and politician who served as the 15th vice president of the United States from 1861 to 1865, during President Abraham Lincoln's first term. He was the first Republican ...

: Maine politician and vice president during Lincoln's first term

* Friedrich Hecker

Friedrich Franz Karl Hecker (September 28, 1811 – March 24, 1881) was a German lawyer, politician and revolutionary. He was one of the most popular speakers and agitators of the 1848 Revolution. After moving to the United States, he served as ...

: leader of the German-American Forty-Eighters

The Forty-Eighters were Europeans who participated in or supported the Revolutions of 1848 that swept Europe. In the German Confederation, the Forty-Eighters favoured unification of Germany, a more democratic government, and guarantees of human r ...

* James M. Hinds

James M. Hinds (December 5, 1833 – October 22, 1868) was the first U.S. Congressman assassinated in office. He served as member of the United States House of Representatives for Arkansas from June 24, 1868 until his assassination by the ...

: Congressman from Arkansas, murdered by the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and ...

in 1868

* William Woods Holden

William Woods Holden (November 24, 1818 – March 1, 1892) was an American politician who served as the List of Governors of North Carolina, 38th and 40th governor of North Carolina. He was appointed by President of the United States, President ...

: Governor of North Carolina in 1868–1871

* Jacob M. Howard

Jacob Merritt Howard (July 10, 1805 – April 2, 1871) was an American attorney and politician. He was most notable for his service as a U.S. Representative and U.S. Senator from the state of Michigan, and his political career spanned the Amer ...

: senator from Michigan

* Timothy Otis Howe: senator from Wisconsin

* George Washington Julian

George Washington Julian (May 5, 1817 – July 7, 1899) was a politician, lawyer, and writer from Indiana who served in the United States House of Representatives during the 19th century. A leading opponent of slavery, Julian was the Free Soi ...

: representative from Indiana and principal framer of the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Fifteenth Amendment (Amendment XV) to the United States Constitution prohibits the federal government and each state from denying or abridging a citizen's right to vote "on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude." It was ...

* William Darrah Kelley

William Darrah Kelley (April 12, 1814 – January 9, 1890) was an American politician from Philadelphia who served as a Republican Party (United States), Republican member of the U.S. House of Representatives for Pennsylvania's 4th congressiona ...

: representative from Pennsylvania

* Samuel J. Kirkwood

Samuel Jordan Kirkwood (December 20, 1813 – September 1, 1894) was an American politician who twice served as governor of Iowa, twice as a U.S. Senator from Iowa, and as the U.S. Secretary of the Interior.

Early life and career

Samuel Jordan ...

: senator from Iowa

* James H. Lane: senator from Kansas and leader of the Jayhawker

Jayhawkers and red legs are terms that came to prominence in Kansas Territory during the Bleeding Kansas period of the 1850s; they were adopted by militant bands affiliated with the free-state cause during the American Civil War. These gangs we ...

s abolitionist movement

* John Alexander Logan

John Alexander Logan (February 9, 1826 – December 26, 1886) was an American soldier and politician. He served in the Mexican–American War and was a general in the Union Army in the American Civil War. He served the state of Illinois as a ...

: senator from Illinois

* Owen Lovejoy

Owen Lovejoy (January 6, 1811 – March 25, 1864) was an American lawyer, Congregational minister, Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist, and Republican United States Congress, congressman from Illinois. He was also a "conductor ...

: representative from Illinois

* David Medlock, Jr: Texas House of Representatives for the 12th Texas Legislature - 1870 to 1873 and was on the Federal Relations Committee.

* Lot Myrick Morrill

Lot Myrick Morrill (May 3, 1813January 10, 1883) was an American statesman and accomplished politician who served as the List of Governors of Maine, 28th Governor of Maine, as a United States Senate, United States Senator, and as United States S ...

: senator from Maine and Secretary of the Treasury under the Grant Administration.

* Oliver P. Morton

Oliver Hazard Perry Throck Morton (August 4, 1823 – November 1, 1877), commonly known as Oliver P. Morton, was a U.S. Republican Party politician from Indiana. He served as the 14th governor (the first native-born) of Indiana during the Amer ...

: Governor of Indiana (1861–1867) and senator

* Franklin J. Moses, Jr.: Governor of South Carolina in 1872–1874

* Samuel Pomeroy

Samuel Clarke Pomeroy (January 3, 1816 – August 27, 1891) was a United States senator from Kansas in the mid-19th century. He served in the United States Senate during the American Civil War. Pomeroy also served in the Massachusetts House of ...

: senator from Kansas

* Harrison Reed: Governor of Florida in 1868–1873

* Samuel Shellabarger

Samuel Shellabarger (18 May 1888 – 21 March 1954) was an American educator and author of both scholarly works and best-selling historical novels.

Born 18 May 1888 in Washington, D.C., Shellabarger was orphaned in infancy, upon the death of bot ...

: representative from Ohio and principal drafter of the Civil Rights Act of 1871

* Rufus Paine Spalding

Rufus Paine Spalding (May 3, 1798 – August 29, 1886) was a nineteenth-century politician, lawyer and judge from Ohio. From 1863 to 1869, he served three terms in the U.S. House of Representatives. He also served as a justice of the Ohio Su ...

: representative from Ohio who took a leading role in the Congressional debates over Reconstruction

* Edwin McMasters Stanton: Secretary of War under the Lincoln and Johnson administrations

* Thaddeus Stevens

Thaddeus Stevens (April 4, 1792August 11, 1868) was a member of the United States House of Representatives from Pennsylvania, one of the leaders of the Radical Republican faction of the Republican Party during the 1860s. A fierce opponent of sla ...

: Radical leader in the House from Pennsylvania

* Charles Sumner

Charles Sumner (January 6, 1811March 11, 1874) was an American statesman and United States Senator from Massachusetts. As an academic lawyer and a powerful orator, Sumner was the leader of the anti-slavery forces in the state and a leader of th ...

: senator from Massachusetts, dominant Radical leader in the Senate and specialist in foreign affairs who broke with Grant in 1872

* Albion W. Tourgée: novelist

* Lyman Trumbull

Lyman Trumbull (October 12, 1813 – June 25, 1896) was a lawyer, judge, and United States Senator from Illinois and the co-author of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Born in Colchester, Connecticut, Trumbull esta ...

: senator from Illinois with strongly anti-slavery sentiments, but otherwise moderate

* Daniel Phillips Upham: Arkansas politician-soldier who was ruthless in campaign that would temporarily rid the South of the Ku Klux Klan

* Benjamin Franklin Wade: senator from Ohio, he was next in line to become president if Johnson was removed

* Henry Clay Warmoth

Henry Clay Warmoth (May 9, 1842 – September 30, 1931) was an American attorney and veteran Civil War officer in the Union Army who was elected governor and state representative of Louisiana. A Republican, he was 26 years old when elected as 23 ...

: Governor of Louisiana in 1868–1872

* Elihu Benjamin Washburne

Elihu Benjamin Washburne (September 23, 1816 – October 22, 1887) was an Americans, American politician and diplomat. A member of the Washburn family, which played a prominent role in the early formation of the Republican Party (United States), ...

: representative from Illinois

* George Henry Williams

George Henry Williams (March 26, 1823April 4, 1910) was an American judge and politician. He served as chief justice of the Oregon Supreme Court, was the 32nd Attorney General of the United States, and was elected Oregon's U.S. senator, and serve ...

: senator from Oregon (1865–1871) and attorney general under President Grant

* Henry Wilson

Henry Wilson (born Jeremiah Jones Colbath; February 16, 1812 – November 22, 1875) was an American politician who was the 18th vice president of the United States from 1873 until his death in 1875 and a senator from Massachusetts from 1855 to ...

: Massachusetts Senator, chairman of the Senate Military Affairs Committee during the Civil War, and vice president under Grant

* James F. Wilson: representative from Iowa, chairman of the House Judiciary Committee during the impeachment of President Johnson and senator from Iowa

* Richard Yates: Governor of Illinois in 1861–1865 and Senator

Notes

References and further reading

Secondary sources

* * * * * Re Michigan SenatorZachariah Chandler

Zachariah Chandler (December 10, 1813 – November 1, 1879) was an American businessman, politician, one of the founders of the Republican Party, whose radical wing he dominated as a lifelong abolitionist. He was mayor of Detroit, a four-term sen ...

*

* 567 pages, intense anti-Radical narrative by prominent Democrat

*

* Major critical analysis.

* A major scholarly biography

*

* Major synthesis; many prizes

* Abridged version

* Lincoln as moderate and opponent of Radicals.

* Keith, LeeAnna. ''When It Was Grand: The Radical Republican History of the Civil War'' (2020excerpt

als

online review

* * Pulitzer Prize. * * Hostile * Pulitzer Prize. * A major biography completed by

Richard N. Current

Richard Nelson Current (October 5, 1912 – October 26, 2012) was an American historian, called "the Dean of Lincoln Scholars", best known for ''The Lincoln Nobody Knows'' (1958), and ''Lincoln and the First Shot'' (1963).

Life

Born in Colorado ...

upon Randall's death.

* Volumes 6 and 7. Highhy detailed political narrative.

*

*

*

* Scholarly history

*

*

*

*

*

*

* Favorable to Radicals

* Favorable biography.

*

* Hostile to Radicals

* 2 vol.

Primary sources

''Harper's Weekly''

news magazine

Barnes, William H., ed. ''History of the Thirty-ninth Congress of the United States.'' (1868)

useful summary of Congressional activity. * Blaine, James.''Twenty Years of Congress: From Lincoln to Garfield. With a review of the events which led to the political revolution of 1860'' (1886). By Republican Congressional leade

full text online

* Fleming, Walter L. ''Documentary History of Reconstruction: Political, Military, Social, Religious, Educational, and Industrial'' 2 vol (1906). Uses broad collection of primary sources; vol 1 on national politics; vol 2 on state

full text of vol. 2

* Hyman, Harold M., ed. ''The Radical Republicans and Reconstruction, 1861–1870''. (1967), collection of long political speeches and pamphlets. *

Edward McPherson

Edward McPherson (July 31, 1830 – December 14, 1895) was an American newspaper editor and politician who served two terms in the United States House of Representatives, as well as multiple terms as the Clerk of the House of Representative ...

'' The Political History of the United States of America During the Period of Reconstruction'' (1875)

large collection of speeches and primary documents, 1865–1870, complete text online.

he copyright has expired.

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' in ...

* Palmer, Beverly Wilson and Holly Byers Ochoa, eds. ''The Selected Papers of Thaddeus Stevens'' 2 vol (1998), 900 pp; his speeches plus and letters to and from Stevens

* Palmer, Beverly Wilson, ed/ ''The Selected Letters of Charles Sumner'' 2 vol (1990); vol 2 covers 1859–1874

Charles Sumner, "Our Domestic Relations: or, How to Treat the Rebel States" ''Atlantic Monthly'' September 1863

early Radical manifesto

Yearbooks

* ''American Annual Cyclopedia...1868'' (1869)online

highly detailed compendium of facts and primary sources; details on every state * ''American Annual Cyclopedia...for 1869'' (1870

online edition

''Appleton's Annual Cyclopedia...for 1870''

(1871)

''American Annual Cyclopedia...for 1872''

(1873) * ''Appleton's Annual Cyclopedia...for 1873'' (1879

online edition

''Appleton's Annual Cyclopedia...for 1875''

(1877) * ''Appleton's Annual Cyclopedia ...for 1876'' (1885

online edition

''Appleton's Annual Cyclopedia...for 1877''

(1878) {{Reconstruction era 1854 establishments in the United States 1877 disestablishments in the United States * American Civil War political groups Factions in the Republican Party (United States) Reconstruction Era Civil rights in the United States